Decentralized finance has allowed the emergence of autonomous protocols whose functionalities are ensured by smart contracts that are sometimes immutable. It enables individuals from all over the world to use financial services that are at the same time sovereign, accessible, and more efficient and resilient than those available in traditional finance. It’s the lovely story that newcomers are told to lull them to sleep: the reality is much more nuanced.

Indeed, a handful of protocols fit this reality, but most are far from being up to par. When the bulls are out, interest in the resilience of the protocols is generally shallow: the only thing that matters is price appreciation. But the bears have made a comeback, and thankfully it means a renewed interest in these topics.

The recent implosion of the Luna ecosystem and its associated stablecoin, UST, will hopefully serve as a wake-up call for some. It was, unfortunately, a perfectly avoidable disaster. The model used for this stablecoin and its flaws were already known, with many previous instances covered on this blog: BAC, MIC, ESD, DSD, etc. (at the application level on Ethereum rather than the protocol level, but with the same fundamental problems). They all had the same end: an endless spiral that brought them closer to absolute 0.

In the face of this event, many investors have become aware that not all stablecoins are created equal and seek to learn more about the resilience of the many stablecoins available on the market and the robustness of different DeFi protocols in general. Therefore, I’m seizing this exceptional moment to discuss this essential topic for the sustainability of DeFi; it has been a passion of mine for a long time.

Indeed, last year I already proposed to you an exhaustive analysis of the risks incurred on the borrowing services in DeFi and how to evaluate them. This article is still relevant and a highly recommended read for any informed investor.

Enough with the introduction. Let’s get to the point and define the term “unstoppable” and what it implies in concrete terms at a protocol level.

What is an unstoppable DeFi protocol?

At the most basic level, we can call a DeFi protocol unstoppable 1 when its essential functions are provided by smart contracts that are not modifiable, and it does not require external intervention to subsist.

To this relatively straightforward definition, I must add many notes and clarifications to cover the diversity of DeFi protocols and their use cases.

⚠️ Third-party protocol dependencies

In DeFi, it is infrequent that a protocol does everything by itself. More often than not, a given protocol relies on various third-party protocols. Of course, the most common and well-known case is the oracle - the source of prices for assets - a critical component for borrowing services in particular.

Dependence on oracles like ChainLink

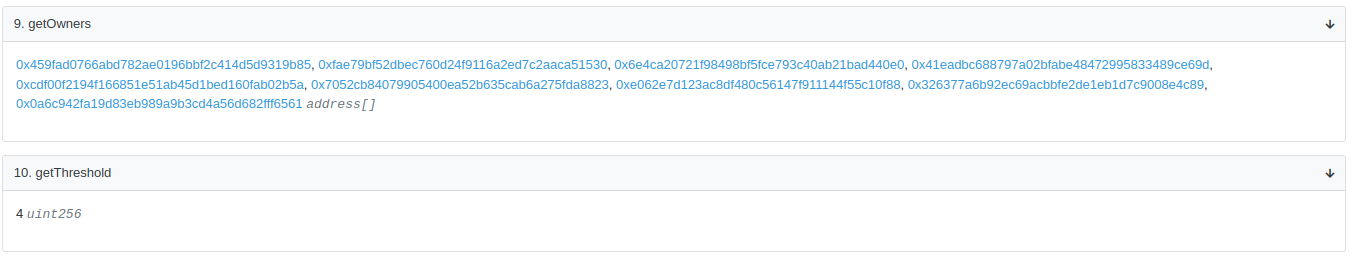

In this regard, the most widely used oracle is ChainLink. Although technically robust, the industry recently got a reminder, thanks to Chris Blec and a few other actors concerned about the resilience of the service: ChainLink’s oracles are susceptible to manipulation or censorship. The riskiest attack vector seems to be the 3/20 multisig, which allows the price source for a given asset to be changed immediately.

Concretely, if three people synchronize among these 20, they could change the ETH/USD oracle, for example, for an in-house oracle that returns a price of $1, and almost all DeFi loans would be liquidated in the process. However, it seems rather unlikely that people on or close to the ChainLink team would carry out such an attack.

The most significant risk seems to be an attack by an external actor who would like to harm the whole of DeFi. Indeed, with such a permissive multisig, it would be “enough” to identify three or more members of this multisig, kidnap them and threaten them to change a price source of ChainLink. It is the famous “🔧 wrench attack.” No matter how secure the smart contracts are, if they are administered by a multisig, they are vulnerable to this type of attack that goes through the people behind the protocols rather than the code directly.

The main problem here is not the existence of this multisig, which is necessary to update and improve the services that ChainLink provides, but its setting:

- 3/20 is extraordinarily permissive and riskier from a 🔧 wrench attack point of view than 3/6, for example (which would have fewer potential targets to perform the attack). A more reasonable number aligned with what is usually done for 20 signers in total would be something between 8 and 12 signers required.

- No timelock: so changes are immediate.

⚠️ Update - May 27: On May 23rd (5 days after the publication of this article), the Multisig setup has been updated to a 4/9, which makes a 🔧 wrench attack harder to perform; there is still no timelock2.

Dependence on other protocols that are less resilient than the base protocol

One of the fascinating elements in DeFi is composability: protocols integrate and use each other. While this allows for the emergence of synergies and innovative use cases, it also comes with additional risks.

Without going into too much detail, as we will come back to it later, we will take as an example PoolTogether, one of the most resilient protocols of the DeFi and quasi-unstoppable. The quasi comes from its external dependencies and, more precisely, the sources of yields used: Compound or Aave.

Indeed, the smart contracts of PoolTogether are immutable except for the part that manages the price allocation (v4). Still, the funds are deployed in protocols powered by smart contracts that can be altered (such as adding a new collateral, a necessary feature but also a potential attack vector3)

The general rule is that a protocol is as resilient as the weakest link in its composability chain. This rule is not absolute, as it is still possible to mitigate or contain the exposure taken with integrations, for example, by implementing redundancy, as we will see below in the detailed assesments.

⚠️ Access to protocols: the question of websites (front-end)

On this topic, there are two key questions:

- Is the access point to the protocol (= the website/front-end) resilient / can it be censored, for example, by a state actor?

- Is the site secure? Can a malicious actor attack it?

Risk of censorship of the front-end

Here, I must start by reminding you of a fundamental point: a DeFi service exists thanks to a set of smart contracts. It is entirely possible to interact with any DeFi service by going directly through the contracts - and thus, even if their site were to be inaccessible. Of course, not all DeFi users have the technical skills required to interact with smart contracts directly, which is why the front-end issue remains essential.

Thus, protocols that maximize their resilience need to think about it. Two main approaches are possible and can be combined.

First, a protocol can have multiple access points that allow access to its service: if one of them were inaccessible, others would remain online, thus causing only minor inconvenience to the service users. For example, Aave can be used through the main app.aave.com site, but also through tools like DeFiSaver, InstaDapp and many others.

Nevertheless, most of these sites are still hosted by centralized services that could all be censored simultaneously: it’s more work, but it’s technically possible. To overcome this limitation, another option is available: having one or more sites hosted via a decentralized solution like IPFS.

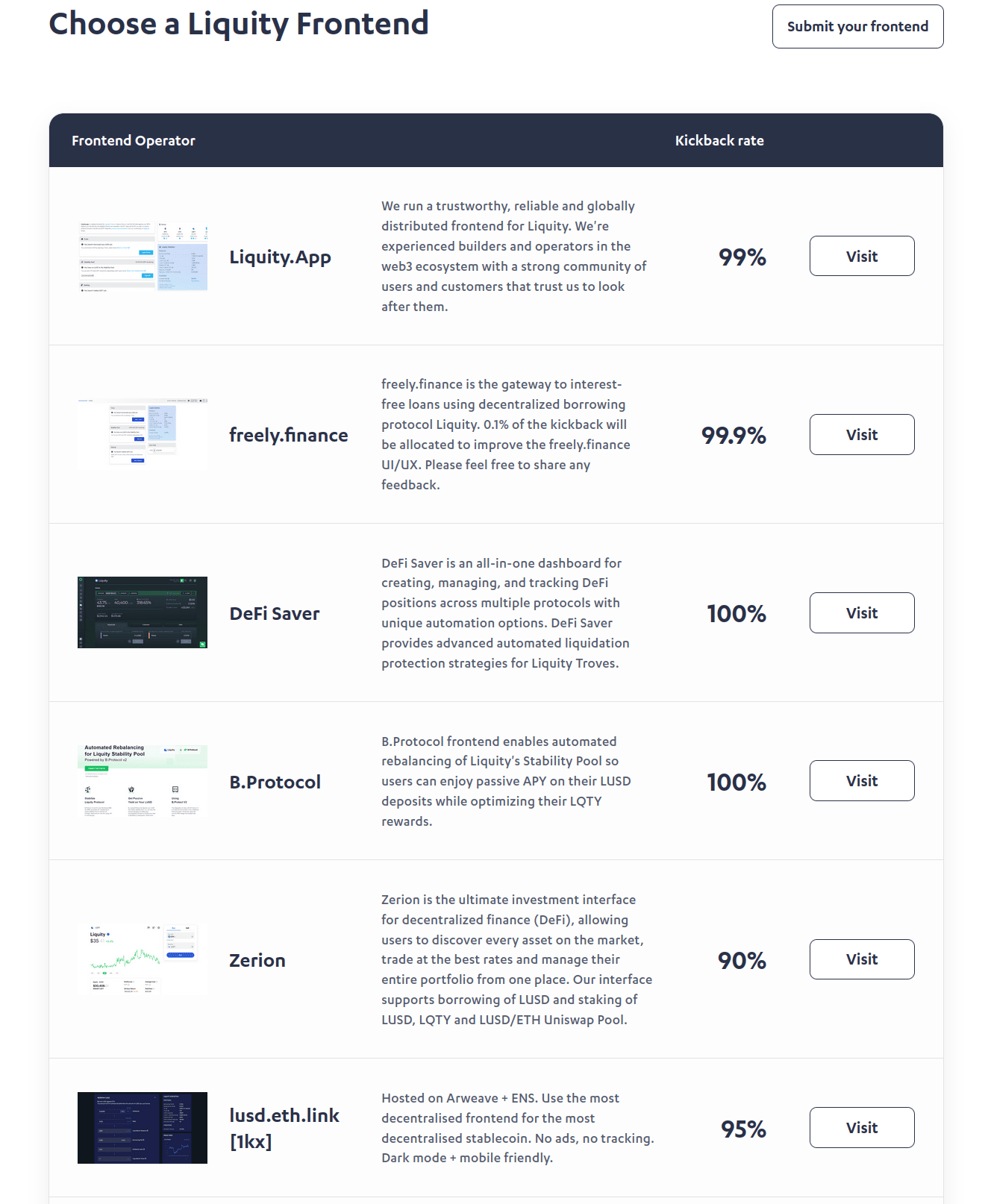

Finally, in terms of front-end resilience, the most original, elegant, and efficient approach deployed to date is probably the one of Liquity protocol. Indeed, Liquity does not have an official website for its application deployed and managed directly by the team. Instead, the team provides a kit to deploy a front-end of Liquity, usable by all. Because of this approach, the project now has a myriad of different sites to use its service, some of which are hosted on IPFS:

Security risks of front-end

Finally, one should not forget that a front-end remains a website. Even if it is not censored, it may be susceptible to attacks of varying degrees of severity: the websites of the decentralized exchange SpiritSwap and QuickSwap, for example, have recently suffered from such a scenario.

The attack vector is linked to the service’s domain name manager (GoDaddy). Other types of attacks are possible: for example, code injections through a third-party service that the site integrates, as we recently saw on EtherScan, as an advertising tracker they use was compromised (CoinZilla).

ℹ️ Limitations of unstoppable protocols

Unstoppable protocols cannot cover all use cases. Indeed, depending on the complexity of a protocol, it is sometimes impossible to avoid any dependency on another protocol that is itself at least partially censurable.

Finally, one must keep in mind the counterpart that comes with the immutability of the smart contracts of unstoppable protocols: an update of these is technically impossible.

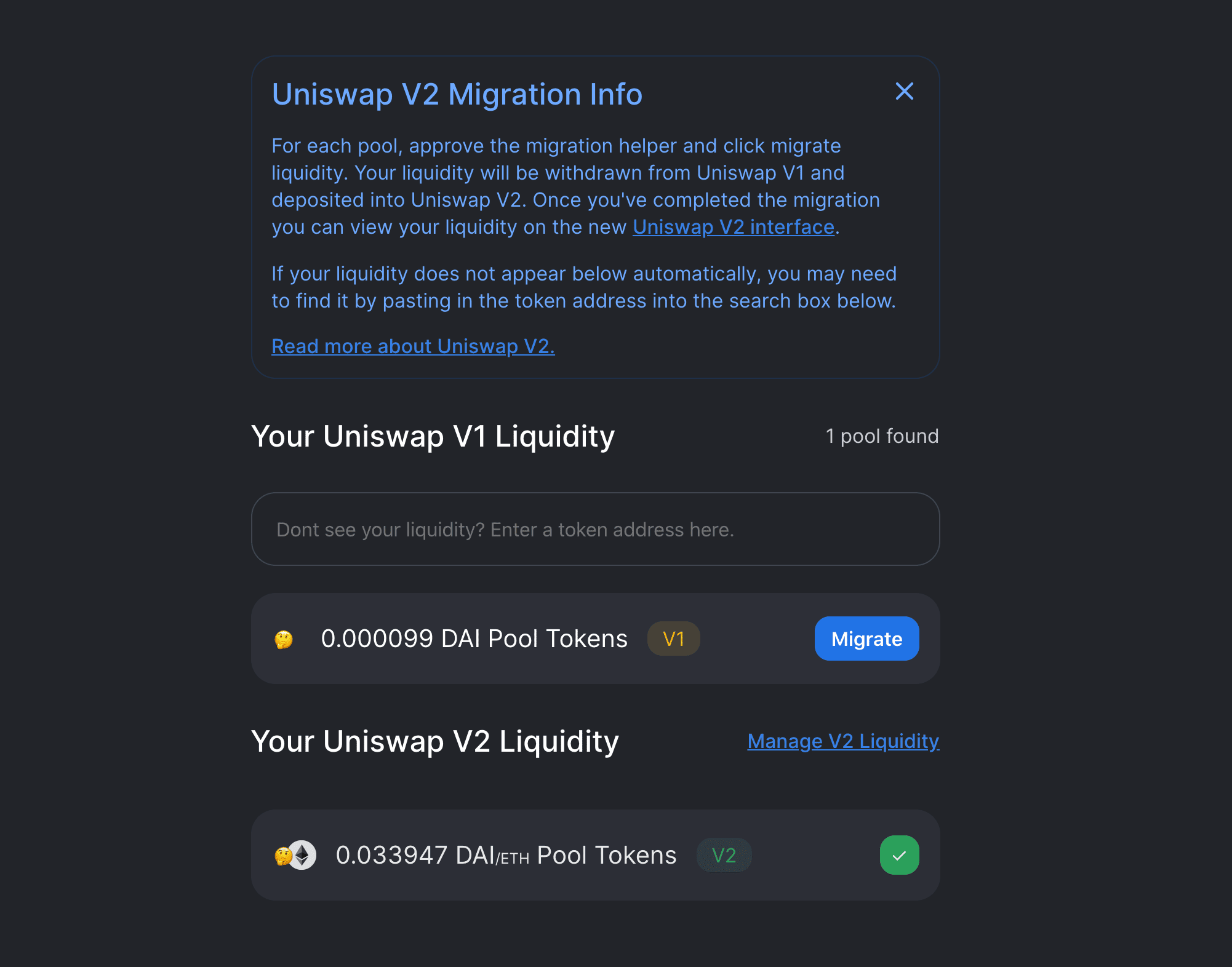

Thus, when an unstoppable protocol needs to evolve, there is only one possible path: deploy a new version of the protocol (with its new set of immutable contracts) and encourage the migration of its users to it. This is, for example, what Uniswap has done twice, with the migration to version 2 in May 2020 4 and then again one year later with the release of Uniswap v3 in May 2021 5.

Depending on the differences between the versions, the protocol may also offer a tool to facilitate migration, as was the case for UNIv1⇒UNIv2. However, it was impossible for UNIv2⇒UNIv3 mainly because of the introduction of liquidity concentration.

Note

To be exhaustive on the cost/benefit analysis of immutable contracts, don’t forget that they make 🔧 wrench attacks impossible and may also be of interest from a legal perspective.

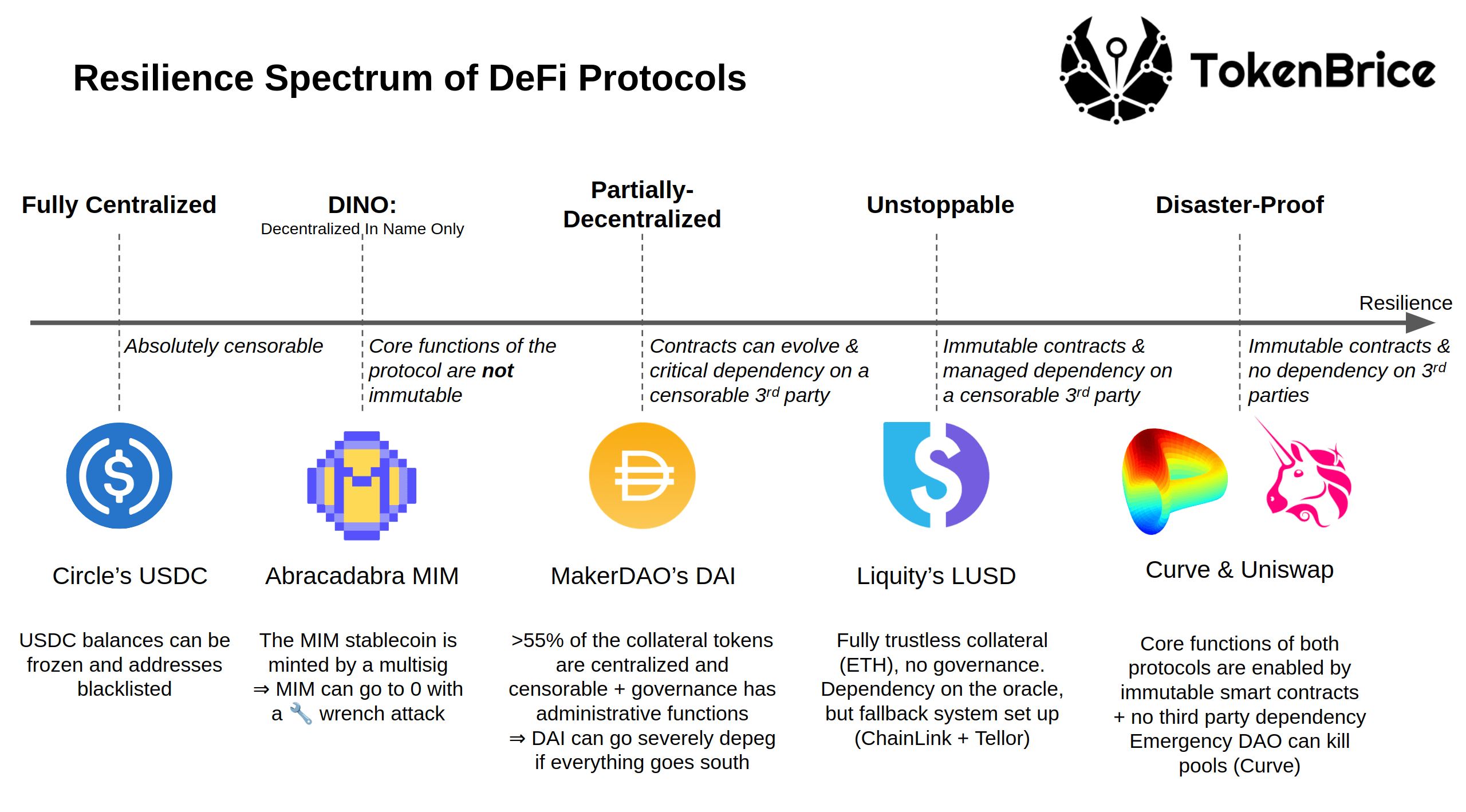

The Spectrum of Resilience

Now that we’ve established the definition of “unstoppable” with all the necessary precisions, I propose to move directly to the analysis. Before digging into the relevant protocols, let me offer you a spectrum that highlights different levels of resilience:

Detailing centralized or “DINO” (Decentralized in Name Only) protocols, decentralized in name only, is not very insightful, so I will let you dig for yourself. Instead, let’s look at protocols on the more exciting end of the spectrum: to the right of MakerDAO.

Analysis of the most resilient DEX

Before we get to the resilience of Uniswap and Curve, we need to recall a few crucial things about decentralized exchanges. Specifically, they have two types of users who assume pretty different levels of risk:

- Users who exchange tokens through the DEX. These users bear the risks linked to the DEX smart contracts for the time of the swap only (as well as those related to unlimited “approve” if the DEX contract is compromised and is not immutable)

- Liquidity providers are exposed as long as their position is maintained.

On Uniswap as on Curve, the contracts relating to the two situations are immutable. It is technically impossible to envisage a “rug” of the liquidity providers, which is not the case for all DEXs: such an attack was possible on SushiSwap once because of their migration function. 6

Please note that DEXs relying on an Automated Market Maker such as Uniswap or Curve do not need an oracle to work, which significantly reduces their dependency on potentially censorable third-party services.

Finally, even if the contracts are immutable, the risk is not zero for the liquidity providers who assume all the risks related to the tokens involved in the pair. The general rule here is similar to that of the composability chain: a given LP position is as risky as its most dangerous token.

Note

The front-end issue for DEX is less critical since many access points exist. The most competent users go through a decentralized exchange aggregator, like ParaSwap.

Uniswap

The contracts core functions are completely immutable on Uniswap v1, v2 and v3. The Uniswap V2 release markededthe introduction of an administrative fee the governance can decided to turn on7 (= to the protocol), as already seen on Curve.

Here, the case is straightforward. If there is indeed a governance, the good news (less for UNI holders) is that what it can do is very limited. No seizure or migration of funds is possible. Apart from the fee, it manages matters such as deploying Uniswap on a new chain, adding a new tier of fees (1bps for stablecoins), or using the protocol’s treasury 8, for example, to fund liquidity mining campaigns or to distribute UNI to friendly people who ask for it, without any limit or accounting 9.

Curve Finance

Curve Finance is another example of resilient DEX with an equally exciting approach. Again, the essential functions are provided by immutable contracts. Nevertheless, Curve also has an “Emergency DAO” whose members are elected by the governance. This Emergency DAO can “kill” a pool (only if pools that are younger than 2 months old and not factory pools): all functions except withdrawal are disabled. It prevents further loss of funds if a problem emerges with Curve’s contracts. The Emergency DAO can also kill a gauge - that is the reward contract handling CRV (and potentially other token) rewards. Killed gauges can then be resurrected by the main DAO.

Like Uniswap, Curve’s governance is centered around the management of CRV token issuance and management. However, the model is much more refined here; I invite you to read my previous articles on the subject to better understand it:

- ⚔ CRV War: Understanding the race to accumulate the ability to influence the Curve Finance protocol

- ⚔ Advanced CRV Wars: Analysis of Protocols Built on Curve and Convex

Unlike Uniswap, participation in Curve’s governance requires locking CRV tokens ( ⇒veCRV) for up to four years for those who want to maximize their influence. Thus, it protects the governance from different types of attacks.

Finally, the governance also manages a whitelist of smart contracts authorized to interact with the veCRV contract 10: such decisions are consequential for liquidity providers on Curve and CRV owners in the long run.

Note

Curve’s governance is one of the most fascinating to follow in DeFi. To help it make more informed decisions, a newsletter offering risk assesments of the various protocols that require a gauge has been set up. I highly recommend reading it; it’s an excellent source for perfecting one’s understanding of risk in DeFi.

In-depth analysis of other notable protocols

In addition to decentralized exchanges, other types of protocols get as close as possible to the most resilient end of the spectrum. Nevertheless, the use cases of the protocols we will detail now are more complex and cannot be served, to my knowledge, without dependencies on other more or less censorable services.

Liquity

Liquity is a dogged project that aims to create the most resilient borrowing system and stablecoin while maintaining an economically efficient system for borrowers. I won’t go into too much detail about this protocol here, I invite you to read the dedicated article.

So let’s focus on the points relevant to our topic of the day:

- Liquity’s code is entirely immutable.

- Liquity has no governance.

- Nevertheless, like any borrowing service, Liquity depends on an oracle (ETH price in USD). Here, ChainLink is used, but a backup system is also in place. Calculations are made to determine if the data provided by ChainLink is deemed reliable. If it is not, the system automatically switches to a secondary price source as long as it is needed: the Tellor oracle. 11

- Finally, as I mentioned above, Liquity also has an interesting approach to maximizing front-end decentralization.12

Thanks to this approach, Liquity is the most resilient borrowing protocol available on Ethereum, allowing LUSD to sweep the title of the most robust and decentralized stablecoin.13

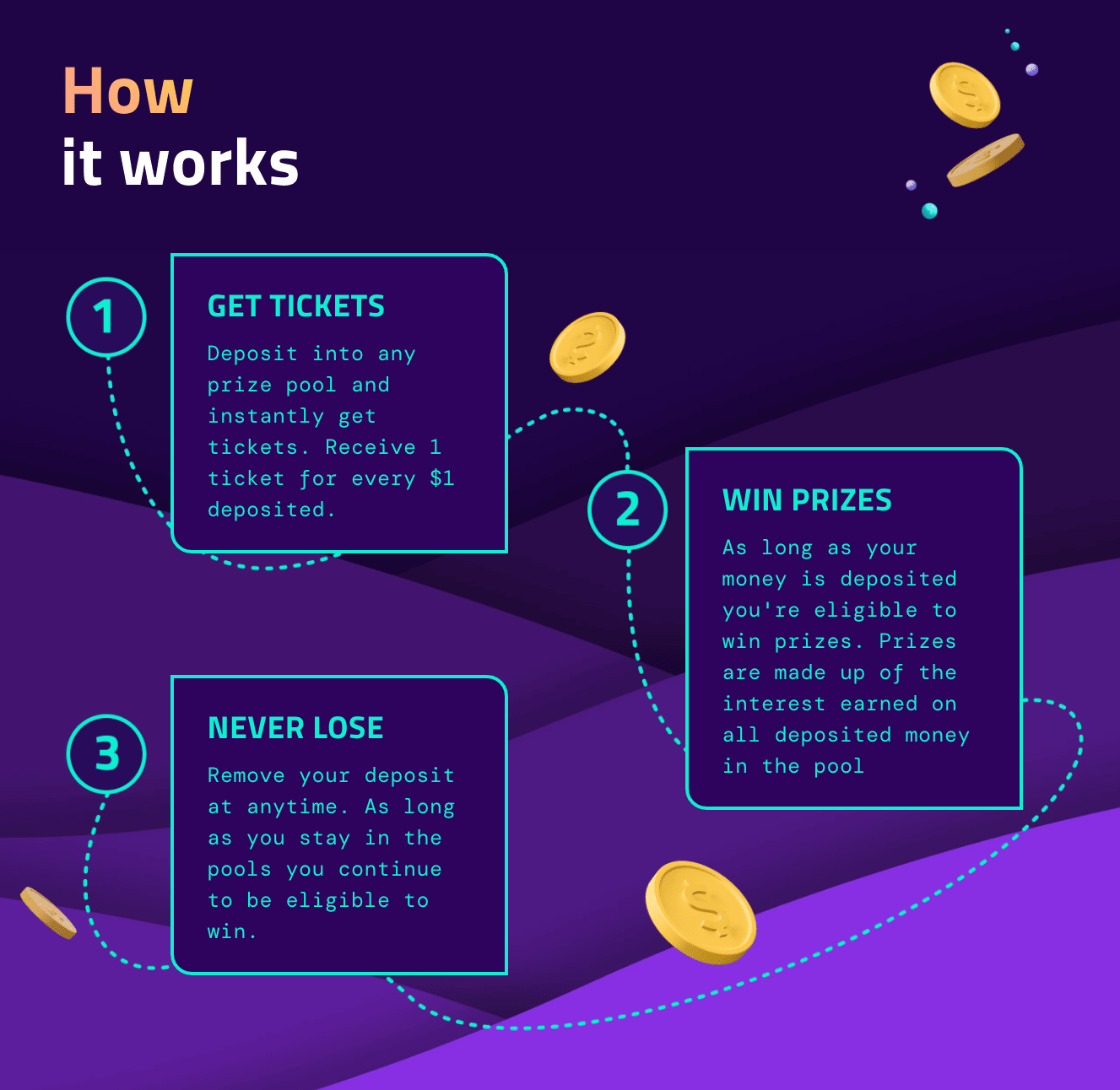

PoolTogether

PoolTogether is a fascinating protocol that explores a new concept: “no-loss”. Concretely, PoolTogether is a prize-linked savings account where the player takes no financial risk on his principal: the game relies entirely on the yield produced by the principal. It redistributes it to the different players according to their luck at the draw.

To learn more about this protocol, I invite you once again to read the dedicated article.

So let’s analyze the resilience of the protocol. Here, the main issue is the initial source of yield, which is external: it comes from services like Aave or Compound, which are not unstoppable. Thus, a PoolTogether player assumes this risk on his entire deposit: the principal and the yield generated (before it is collected and redirected).

Despite this third-party dependency, the PoolTogetger protocol is remarkably resilient. Indeed, on the PoolTogether side, contracts are as immutable as possible. Specifically, they are all immutable (so a given pool cannot change its source of yield), except for the prize distribution part, which only affects the yields generated. Indeed, the prize distribution model can change following a governance vote (mainnet) or a multisig operation (Avalanche/Polygon), which is necessary because cross-chain governance is not yet available.

This point is fascinating and unique in DeFi: PoolTogether is a no-loss prize-linked savings account. This (financial) design principle also manifests itself in smart contracts. A player cannot lose his principal, excluding a problem with Aave/Compound or a critical bug in the PoolTogether contracts. The code itself guarantees this; only the return is potentially at risk. Even if the entire PoolTogether team suffers a 🔧 wrench attack or PoolTogether’s governance turns hostile. So the promise of no loss is upheld at the smart-contract level.

There are also nuances and differences between V3 and V4 of the protocol as far as risks are concerned. The best thing is to carefully read the documentation.

TrustlessFi 🏗️

Trustless is a protocol that I’ve been fascinated with lately. It’s not live yet, but I think the approach has a lot of merits. To describe it very simply, TrustlessFi is like Liquity and Reflexer having a child together on zkSync.

So the goal is, as with Liquity, to create a protocol that will eventually be as unstoppable as possible, and the associated stablecoin (HUE) will inherit this property. Other mechanisms are similar to Liquity, such as ETH as the only collateral, immediate liquidations, or decentralization of the front-end (with a community validation mechanism this time).

On the governance side, we have here an approach similar to the Reflexer/RAI de-governance plan but more engaging: 4 phases are envisaged, and at each stage, the control of the Foundation and the community decreases making the protocol more and more immutable. These phases will be implemented in the code of the contracts themselves: it is possible to delay the transition to a new phase by 45 days up to three times if necessary, but it is impossible to cancel this transition altogether.

A mechanism similar to Maker-MCD’s Dai Saving Rate allows participation in the system without necessarily needing to generate debt. HUE owners will be able to stake it to get a return from the interest rates paid by the borrowers.

Finally, there are also some fascinating new features, such as that Troves/CDPs will be tokenized as NFTs, allowing their transfer. Another example is the deployment of HUE liquidity in Uniswap v3 (HUE/ETH), managed by the protocol. At the oracle level, we would also have an unstoppable price source using Uniswap v3, but this undoubtedly comes with increased manipulation risks.

Overall, the approach is going in the right direction. Still, there are many new concepts in this protocol, so it is not easy to anticipate the result once it is available in production for the time being 14.

Conclusion and last clarifications

I hope that this definite article can serve as a reference for all those who have essential questions about the resilience of DeFi protocols. As usual, rather than delivering assesments as is, I have tried to detail as much as possible the methodology and reasoning so that you can study for yourself the resilience of any protocol not mentioned in this article.

To go deeper, I warmly invite you to read an article I published last year, which perfectly complements this one, focused on money markets. It proposes a method of analysis to evaluate the different potential risks they imply:

Assessing risk in decentralized finance: a handbook for money markets

I imagine that such a precise analysis of such a critical subject could arouse more or less positive emotions. Please know that, as always, my intention is only to inform as many DeFians as possible on matters that I consider essential for DeFi in general.

My educational and pedagogical actions in DeFi have no other purpose than maximizing the resilience and relevance of decentralized finance over the long term. I hope that developers or promoters of protocols to the left of my suggested resilience spectrum will also understand and recognize this mandate.

🙏 A huge thank you to all the proofreaders and contributors who participated in the development of this article:

- Proofreading and clarity of expression: Charles and Disiaque

- Technical and factual proofreading: Taz from DeFi France, MTorgin

Footnotes

I mention throughout this article the unstoppability of some DeFi protocols: we’re talking about the immutability of smart contract code here. The order of transactions on Ethereum can still be manipulated (⇒ MEV), and miners keep an essential role (until the transition to PoS). The contractual unstoppability discussed in this article thus has infrastructural limits. ↩︎

ChainLink provided more info in their documentation and the multisig contract can be checked directly on EtherScan here

Analysis of the incident on Aave’s governance forum. ↩︎

The infamous migrator function, also present in many SushiSwap fork. More information on this dreaded feature in this dedicated Rugdoc article. ↩︎

You can follow the latest discussions on the subject on the Uniswap governance forum. ↩︎

Entirely in UNI token, this treasury is quite volatile. Nevertheless, more than 227M UNI is still available today, or about $1.1B. OpenOrgs ↩︎

This is the infamous 005 “DeFi Education Fund” vote; read the related topic on the governance forum for more context. ↩︎

There are three at present: Yearn Finance (yveCRV), Convex (cvxCRV) and StakeDAO (sdCRV). ↩︎

This article provides a clear introduction to the oracle management system on Liquity. ↩︎

More information on the technical and incentive model for Liquity front-end operators. ↩︎

As you’ve probably already seen, I’m thrilled to have joined the Liquity team very recently. I mention Liquity in this article because it is a relevant and instructive example of resilient protocol, independent of my professional commitments. ↩︎

As always, the alpha is for those who dig in and read footnotes carefully as well as documentation. ↩︎