Deep Work, a book published by Cal Newport in 2016 was highly impactful. While Cal’s writing did not bring anything new to the table, it put the spotlight on an idea that was rarely mentioned outside the psychology circles: the “flow” (also known as “being in the zone”).

“The Deep Work Hypothesis: The ability to perform deep work is becoming increasingly rare, and at the same time it is becoming increasingly valuable in our economy. … the few who cultivate this skill, and then make it the core of their working life, will thrive.”

— Deep Work p.14

Developers took a keen interest for the concept, yet what Cal Newport suggests could apply to any profession. He explores the idea of “committing to depth”: if you manage to achieve a state of deep concentration while you work, you can achieve phenomenal results AND take away pride, accomplishment, and satisfaction from doing it.

It’s easy to understand why his ideas gained attention not only from productivity-buffs but also for people who lost touch with the meaning of their jobs and were looking to reclaim it.

His book touches on other themes related to deep work and its impacts. He addresses the vanity of social media, and the benefits of boredom as well. He also talks about how to **focus **— not a work-related focus but what you decide to focus on as a person — defines your life and what you make of it.

Overall, his book is full of interesting insights. If you find value in this article which overlays its key finding and how to put them into practice, I invite you to read the full book.

Deliberate practice

To reach a state of deep focus and concentration, he advocates for deliberate practice, a concept pioneered by psychologist K.Anders Ericsson. One of his key findings is that the expert’s performance in a given skill has less to do with innate talent and is more likely tied to how the expert deliberately practices being good at it.

We argue that the differences between expert performers and normal adults reflect a life-long period of deliberate effort to improve performance in a specific domain.

— The Role of Deliberate Practice in the Acquisition of Expert Performance

You probably heard about Gladwell 10, 000-Hour rule? He considers it to be the key to success in any field. The theory is appealing considering it gives a clear path to expertise: dedicate the time for it! The rule quickly gained traction in popular culture, despite being debunked.

Indeed, as Ericsson’s research proved, repetition by itself is not enough to become good at a given skill. He lays out the two pillars of deliberate practice, which helps to develop expertise:

- Focusing on a defined perimeter: the path to expertise starts by breaking down the skills required to become one. From here, the wannabe-expert can focus on improving those skillsets during his training or day-to-day activities. It works even better when it’s paired with immediate feedback.

- Continuous and challenging practice: the practice must be frequent (ideally daily) and always challenging. The practice is “deliberate”: the expert practices with the intention of mastering the given skill. This one ties back to grit and perseverance. Focusing on the challenges we struggle with helps us learn faster.

Impacts on motivation and outcomes

Deep work, and deliberate practice impact more than merely our state of concentration, the outcome of our work, and the pace at which we achieve it. Deep states of focus bring more satisfaction from what we do, and a sense of fulfillment.

This increased satisfaction we pull from our work helps us to stay motivated, making it easy to keep dedicating hours to the practice… Essentially, when deliberate practice is adequately set in motion, it creates a virtuous circle of practice, learning, satisfaction, and enjoyment.

Deep work in practice

You have the basics on the theory. You can read Cal Newport’ book, or Ericsson’s paper to research it further. Now let’s see how to implement it in your daily life.

Setting yourself for deep work

Depending on your job and habits, this part can be the easiest as well as the hardest. Basically, to be able to achieve a deep state of concentration you need to set yourself up for success. In practical terms, it means creating a distraction-free work environment. I can’t give you the magic formula of focus, but I can share my personal practices; what follows is my focus setup:

- I set my phone in airplane mode, out of sight.

- I close my communication apps (such as Slack, or Thunderbird)

- All apps unrelated to my current task are closed. I usually only have my editor (Typora), and Firefox opened.

- I categorically refuse all notifications in my browser.

- I have 4–10 tabs maximum opened, all related to my current task.

- If I work in a shared environment, I put my headphones on. It helps me to get in my zone and reduces the physical interruptions from coworkers.

- I put on repetitive electronic music, with little to no lyrics, something like this.

Your setup will probably be different, but you can see a pattern here: reducing interruptions and cutting yourself out from the world to enter your bubble of focus and attention.

Making it work for you

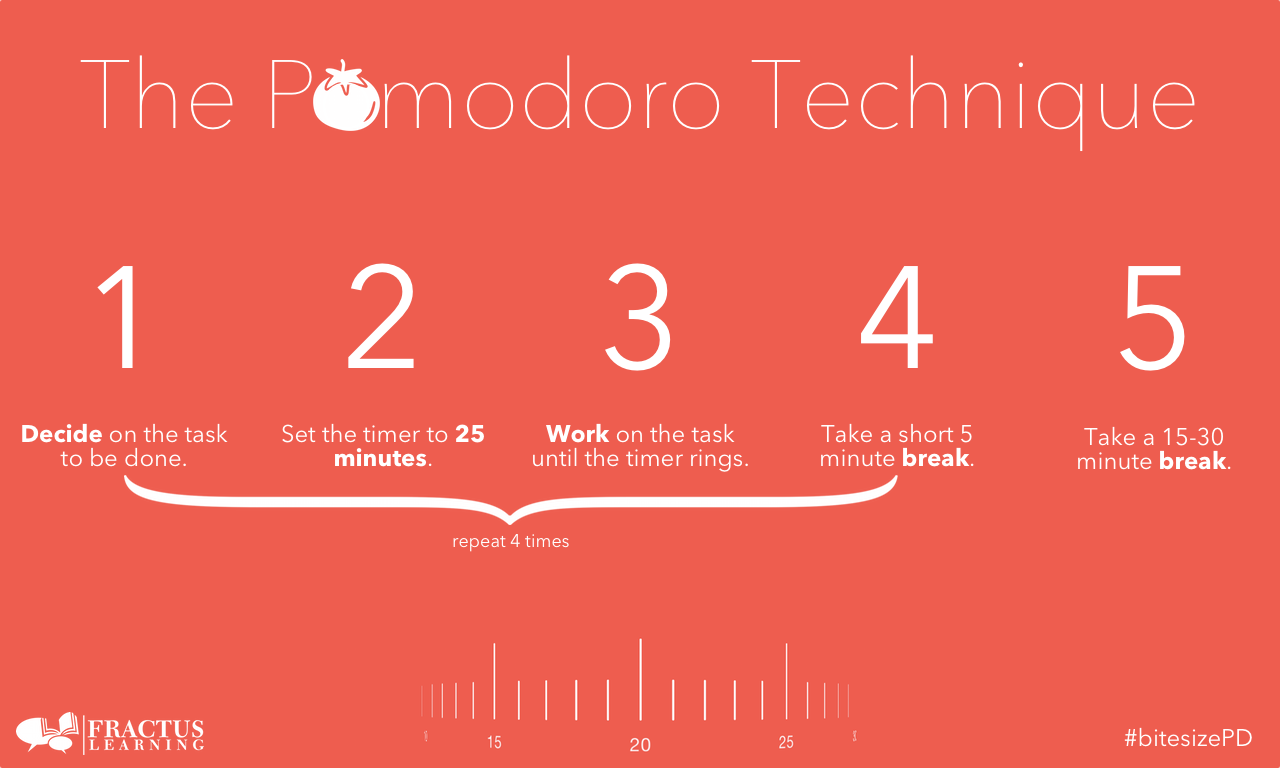

Once you’re all set, it’s time to work and stay focused. You can use different techniques, but there is one particularly useful to get used to working in a highly focused environment: the Pomodoro technique. It’s easy to understand, and supported by many apps available on all kinds of environment.

- Decide on the task you will tackle. It must be unambiguous and well defined.

- Work for 25 minutes (a pomodoro), undistracted, on this one thing.

- Take a short 5-minute break.

- Repeat step 1–3, up to 4 times and then take a longer break (20 min).

The key here is to be able to break up your task in 25 min batches. Some tasks will require several pomodoros, and that’s OK as long as you’re able to break them into smaller consistent tasks.

Breaking goals into small, achievable tasks

A complex task, such as make a landing page for my project is not an executable goal. I need to break it down into smaller steps to realize it using the pomodoro technique:

- Research and analyze landing pages of similar projects, and summarize my main findings. (1–3 pomodoros)

- Draft the content for my landing page (3–4 pomodoros)

- Draft the layout of my landing page (1–2 pomodoros)

- Find a relevant theme/template to use (1 pomodoro)

- Set up the hosting and the theme (1 pomodoro)

- Edit the content on my new landing page (1 pomodoro)

- Set up the template (1 pomodoro)

- Polishing and review (1–3 pomodoros)

Breaking your tasks into smaller chunks help you on so many levels. First, it streamlines the execution. Then it helps to avoid procrastinating. Finally, it makes it much easier to determine how long with the implementation of the given task takes. I cannot estimate make a landing page, but once broke down into eight smaller steps I know I’ll take me between 10 and 16 pomodoros (~6.5h maximum, excluding breaks).

Learning, and be willing to learn

Once you’ve figured it what your deep work environment looks like, and you’ve got the gist of the pomodoro or other productivity techniques, you’ll be able to work much more efficiently. It also works very well for studying and learning new skills. You can also dedicate some time to read on how to learn.

Primarily, it comes down to curiosity. Remember the “challenging practice” I mentioned earlier? Attacking new problems and stepping out of what you already know is the best way to grow. You will also need to be, or become a self-learner. It means being able to fix your issues by yourself.

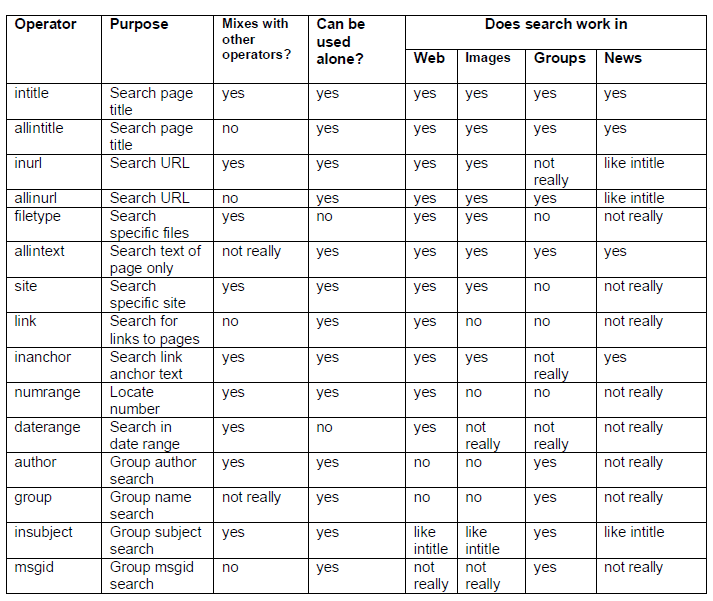

It’s not that hard if you know how to search answers for any given problems. It takes minutes to learn about and master Google search operators.

It benefits all kind of profiles, as you will become much more efficient in your online searches. It helps you to avoid asking for help when it’s not necessary. Save your requests for situations where you’ve covered the widely accessible basics and are still without answers.

Exploring the depths of work

The path to focus is hard. You’ll probably need a few weeks to be able to properly chain a few pomodoros together and start to make the focus time longer, up to 50–60 minutes. You’ll see and feel the benefits of these techniques pretty quickly. It will get more comfortable and easier to achieve a state of flow, and you’ll have breakthroughs.

Good luck on your path to productivity and most importantly: don’t forget to enjoy yourself.