Money is a critical element of our modern societies: a slight change in its mechanisms can have a much broader impact than simply affecting the economy. Therefore, a better comprehension of these mechanisms will give you a better grasp on various topics ranging from Political Economy to cryptocurrencies.

Money is a complex subject, even more lately if we consider all the convoluted systems and protocols that were progressively built on top of it: monetary creation, central banks, inflation… With this piece, we’ll go back to the basics and eventually down to cryptocurrencies: What defines a currency? Why do we need them? What types of currencies do exist?

Buckle up for a quite an adventure in which we discard old but still prevalent tales and propose necessary new ones to make complex mechanisms crystal clear.

The Tale of the Origins of Money

When you hear about currencies, you often get a tale that is easy to understand and compelling; yet it’s just a tale. It goes like this:

At the beginning, we were barterers, the my chicken for your corn kind of deal. Then, since bartering wasn’t efficient, we needed a more standardised mean of exchange: a good that could pass as a store of value. Precious metals were the perfect candidates — they became coins, a form of money.

Yet, later on, those coins evolved once again and became paper money — still a currency, but the origin of their value shifted: while a coin gets its value from its very material (the precious metal it’s made of), the paper money needs an institution to emit it and guarantee its value one way or another.

Finally, in the digital era, money evolved one more time. It’s now all “digital” — just bits, 0 and 1 located somewhere in a server and transiting almost instantly in the fiber network.

We must take our time to methodically deconstruct the tale in order to dismiss it, we’ll learn quite a few things along the way:

Money is not a store of value

Money is not a store of value, it’s a claim upon value.[1]

Let’s burn some cash to understand money better

Let’s study together the example that made the distinction between the two very clear to me: let’s say I burn a $20 bill — will any value be destroyed?

Thanks to the Joker for helping with the experiment

Thanks to the Joker for helping with the experiment

Well… Simply no! What has been destroyed is my ability to claim the aforementioned value: I can’t exchange the ashes of my bill for a beer.

Make it rain!

Understanding the difference between a store of value and a claim upon value allows us to also understand the obsession with circulating currency. Indeed, money is not wealth by itself: as long as the money is not claimed (spent for goods or services), it has no contribution whatsoever to the wealth of the given country.

Let’s go back to our previous cash burning experiment to dig deeper: when I burnt my $20 bill, it had no impact on the GDP (Gross Domestic Product) of the USA. Yet, if I start to burn millions of dollars, we might start to see secondary consequences affecting the GDP: since there will be less money circulating, there might be less people using it to claim value (a beer, clothes…) and therefore an impact on the real economy of the country.

Those secondary consequences will only happen if the cash I burnt was meant to be spent — if burning the bills prevented me from claiming the value they carried. Hence, if I’m a multi billionaire (so let’s assume: incapable of spending all of my money), I can burn millions of dollar without having any impact on the economy: those millions would have never flowed back into the economy anyway.

Putting a stop to the flow of money which would have changed hands without that stop is like preventing others to work to provide value; this value would have been exchanged for currency if the money was circulating freely.

Counterfeit money, real value?

To get over with the myth of money as a store of value, let’s consider a third and last scenario. Let’s say I print a very **well done stash of counterfeit money **— everybody take it for the real one. Now I give out those bills to normal American citizens, and for the sake of the simplicity of this example, the FED doesn’t notice.

In that scenario, the happy citizens who got free real-like yet counterfeit bills will start spending them for goods and services — they will claim what is rightfully theirs because of their ownership of the bills, hence increasing the GDP of the country.

Yet, all of this is a scam, no value was actually created: I only printed and handed out fake bills that people think legit.

Money barely is the key to the gold chest. When money itself, its physical medium, still had value (such as gold or silver coins), the content of the chest was still tied to the amount written on the key. Now, we are in a system where keys are changing endlessly changing hands without ever returning to open the chest. Our trust in our currencies is so high that the amount written on the key is sufficient and even authoritative.

The myth of bartering and its inefficiency

Let’s go back to the first tale about the origin of money presented in the beginning of this article: was bartering really as prevalent as the story make it seems?[2]

We need to place some context to answer this question. We’re talking about a world where money doesn’t exist yet; hell, the very notion of “property” is even clear yet. Of course there were exchanges, but the “exchange protocol” was very different that what we picture behind the idea of bartering.

Premodern agricultural societies were largely self-sufficient: exchanges between the member of a given community followed informal systems based on relationships: the “economy” was powered by gifting and reciprocity.[3]

In practical terms, rather than the my goat for your corn kind of deal, it was more like I will help you build this house because I know how to do it. Later on, you'll help me furnish this other house since you're a skilled woodworker. If you don't, it can put an end to 1/our relationship, 2/your very place in the community

Note: Considering the system depicted above was informal, the “if you don’t…” part didn’t need to be stated, it was understood.

In the premodern agricultural societies depicted above, barter also existed but wasn’t the main mean of exchange: it was useful to be able to exchange with people who didn’t share the kind of relationship we depicted — for exchanges between communities for instance.

The distortion of the Historian’s lens

There could be another reason to explain why the tale of the evolution from bartering to currency is still prevalent. To reconstruct the past, historians use remains found in modern times. Coins stand the test of time. On the opposite, informal gift/counter-gift dynamics barely leave any traces behind them.[4]

Helixism was born when Reddit started to play Pokemon, together (Twitch Plays Pokemon) — The Origin of Ancient Helixism

Helixism was born when Reddit started to play Pokemon, together (Twitch Plays Pokemon) — The Origin of Ancient Helixism

Moreover, the example frequently chosen to illustrate the bartering system are doubtful. We’re talking about goat vs corn deals, but is it realistic in the context of a premodern agricultural society? Since they were mostly auto sufficient, bartering was for goods that weren’t required for the community’s survival, since these were already produced within the community.

DOWNPLAYING THE ROLE OF BANKS

With the tale of the origins of money, banks look like mere intermediary. They provide more or less practical systems allowing the money to flow: it used to be ledgers, and it’s still is but now we have a clunky web interface to write/edit stuff in them.

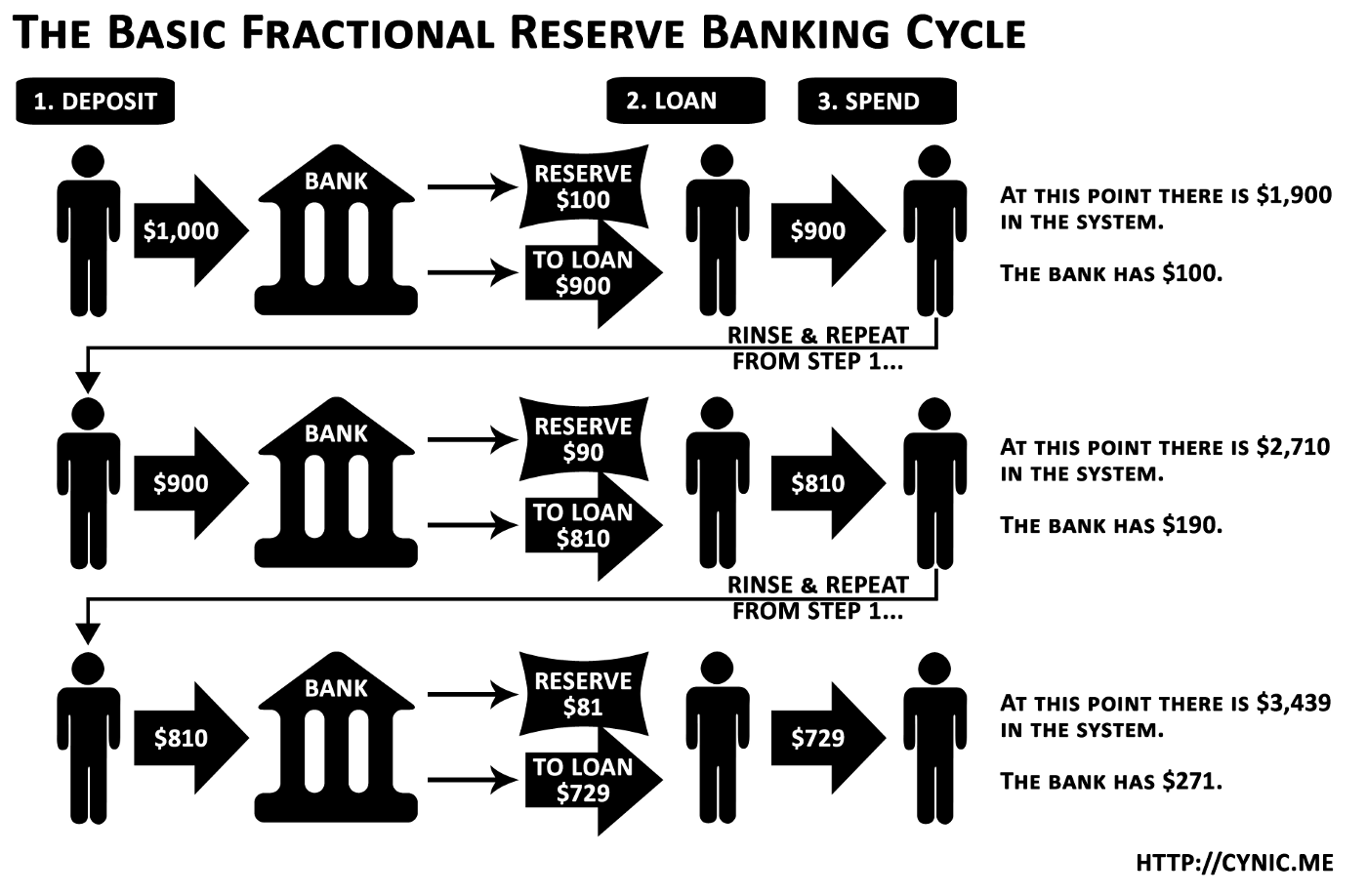

Yet, this skip the crucial role played by banks in our current monetary systems: monetary creation. For the sake of the easy-of-comprehension of this article, I won’t dive into the depths of it in here, a quick presentation of it will have to suffice. This mechanism is called the fractional-reserve banking.[5]

Here is a short and (too) quick explanation — a central bank emit a monetary base allowing commercial banks to issue currency by themselves through loans. When Bob comes to Bank of America for a $10,000 loan, BA is not pulling money from its reserve to credit Bob’s account. No, what happens instead is this: the amount written in Bank of America’s ledger next to Bob’s name is increased by 10,000, and that’s pretty much it. The confidence is the banking system is preserved through mandatory reserve, corresponding to a fraction (~10%) of the loaned amount.[6] Which leads us to our next point.

The myth of bits: a digital ledger is still a good old ledger

Now that we are clear on monetary creation — made by bank and nothing more that an input on a ledger — let’s tackle the last myth surrounding money, the one that states that money became 0 and 1, bits stored somewhere on a server.

In real life, the nature of money hasn’t changed: the good old bank ledger is still authoritative. Its authority comes from the fact that it doesn’t exist in a vacuum: it draws its authority from the whole political, societal and judiciary system that surround it. The way we interact with the ledger (analog or digital) doesn’t reshuffle the decks.

With credit cards, ATMs, online banking and all the others “innovations”, it might seem like our monetary system evolved. In reality, we’re still very close to our first monetary systems and our modern currencies follow pretty much the same rules as the old ones. Innovations and changes happened mostly at the interface level: how we interact with the ledger.

Most of the changes happened at the monetary creation level, it used to be much simpler and a state matter but the rest didn’t budge much. Our modern currencies share more with the Gold Franc[7] - pardon my Frenchness - that we imagine. Disruption has yet to happen on currencies, what we had so far is barely a parade of facelifts.

A sneak peak into the real monetary innovations

We needed to lay out the groundwork in order to finally reach this point, the most interesting part: how does real monetary innovation looks like? The answer is not as simple as “Bitcoin”, it can take many forms:

Change the ledgers’ governance mechanism

Quick reminder: the current trust placed in our ledgers is due to:

- The reputation of the institutions who handle the monetary systems, be it central banks, private banks or other institutions.

- The political, legal and societal framework built around banks.

- The general public ignorance of the mechanisms governing currencies.

You might think it’s not much to hold the whole monetary system afloat; don’t worry, you’re not the only one. Critics have been numerous and early; in the 80s the cypherpunk movement were already looking into alternative currencies to break free from the fiat ones.[8]

Fiat currencies are intrinsically useless objects that serves a medium of exchanges. They only have value because a government maintain and guarantee it.

Cypherpunk experimented with digital currencies and eventually lead us to the Bitcoin introduced by Satoshi. With Bitcoin, the trust in the monetary institutions is no longer required (“trustless”). Indeed, in short the idea is as follows: instead of trusting the banks and other institutions to maintain the ledger, why not make that ledger public (=blockchain) and rely on our peers instead? This system also requires the use of cryptography and mechanisms to reach a consensus on the public ledger (so there is only one), but that will be covered in another article.

Alter the innate propriety of money

What about a currency that depreciates if not used? It would help to keep it circulating. The idea is not new, it was theorised in 1916 already by Silvio Gesell and is called demurrage.[9]

The idea of a currency depreciating over time might seem scary at first as it contradict our intuitive comprehension of money (“how can it be a store of value if its value shrink over time?”). We already have already established that this intuitive comprehension of money was far from the truth of the practical world. This kind of money has an evident interest for recessionary phases, as it promotes spending the money quickly and “punishes” hoarding.

Limit what kind of items money can claim be claimed upon

Without even altering the innate proprieties of money, we can change what it can be exchanged for. Local currencies are a good example of this. If they are designed carefully, this kind of currencies can help revitalize the local economy and independent businesses. Local currencies are plentiful; the Brixton Pound (B£) is one of the most well known. The team behinds it does a pretty good job to explain their thought process.[10]

Conclusion

I hope this article will provide you with a better understanding of money but most importantly that it sparked an interest and it makes you want to learn more about it! The actual monetary innovation has yet to happen. The good news is now that we have cryptocurrencies, it’s much easier to create new ones — pretty much anybody can do it and it’s an excellent news!

It means that all the mechanisms we talked about and many more will be implemented and tested at scale. They already are: there are more than 1500 traded cryptocurrencies and easily another 10 thousands local, confidential or developed for learning purposes. You would like to mint your own coins too? Here’s a guide to get started.

Soon in your wallets: the Brice paper e-Dollar coin pegged on sand

Soon in your wallets: the Brice paper e-Dollar coin pegged on sand

Beyond what blockchain can offer, maybe here lies the most valuable contribution of Satoshi. By creating Bitcoin, he paved the way and reminded the whole world that minting money isn’t reserved to states — it’s the business of regular people too: you, me, us, and even your computer illiterate grandma should have a say.

Like all changes, it sounds scary but if you think twice about it, it makes so much sense: who better than the future users themselves could design the currency the most fitted to their needs?

This article is the translation of an original (French) EcoCrypto.fr story.

SOURCES: TO DIG DEEPER

I would like to give a special acknowledgement to Brett Scott who tremendously helped me to understand what money is and the different mechanisms tied to it. Go check his blog, it’s worth the read!

Money is not a store of value. It is a claim upon value — Brett Scott for The Hectic’s Guide to Global Finance, on March the 10th 2016

Was money created to overcome barte r? — Reynold F. Nesiba for New Economic Perspective, on September the 23rd 2013

The ties that bind: Culture and agriculture, property and propriety in the Newfoundland village fishery — Gerald M.Slider for Social History on May the 30th 2008

The Future of Money Depends on Busting Fairy Tales About Its Past — Brett Scott for Medium — How We Get to Next?, on March the 30th 2016

Fractional-reserve Banking, Wikipedia

Can banks individually create money out of nothing? — The theories and the empirical evidence — Richard A. Werner for the International Review of Financial Analysis, in December 2014

Gold Franc, Wikipedia.

Cypherpunk, Wikipedia

Demurrage (Currency) — Wikipedia

What is the Brixton Pound? — Official website of the Britxton Pound