In a previous article, we raised many issues about the advertising model and free online services in general. They all fall within the spectrum of hidden cost, something society, we, eventually pay for. From recurring annoyances to a loss of political power, the range of consequences of data concentration for political and social influence is wide. Behind all of these “free” offers, compromises are made.

There are many issues with the ad model, all falling under the spectrum of hidden cost. Indeed, behind FB’s “free” offer, a lot of compromises are made, here is a quick overview:

ADVERTISEMENT OVERLOAD

Considering the online services business model, the (infinite) multiplication of ads inevitable. Indeed, it’s the main way for the actor to maximize their revenues. They are essentially caught in a profitable and vicious circle: More ads -> More views, more views -> more sales, more sales -> more money -> more ads.

Since ads are profitable, more and more media space is used to that end. New forms of advertising-content hybrids appeared over the past years, like Native Advertising, as advertisers are looking for new territory to conquer where the consumer resistance is lower. The frontier between a media outlet and a brand outlet is progressively fading out.

On the online side of the industry, the sheer size of the actor should be a cause for concern. Facebook now as 2bn+ users. That’s more than any government, even China or India can’t compete. With this level of mainstream adoption, the reach is virtually unlimited and nobody is out of scope. To continue to personalize its ads further, Facebook amasses detailed profiles for most individuals, that can then be used to influence them.

Facebook is the most influential medium for political and social causes. Concentrating so much power in one space is obviously dangerous, as it makes the social discourse more prone to manipulation and coercion. Yet data is meant to be shared, and advertisers are quite generous when it comes to user data.

COLLECTED DATA ARE LEAKING

Indeed, the frequent exchanges between actors in the industry make the data issue widespread and hardly revocable. Whatever the collect point is, the data gathered will eventually be sold to “independent measurement and data company” like Nielsen or Axciom.

The consumer not only lose control over its data, he also has no knowledge of the usage made of it and who currently owns it. Given enough money and resources, anyone could potentially acquire a very detailed file on anybody, including relatives of course.

The profile is often qualitative enough to let the advertisers and their clients influence opinions, behaviors and ultimately votes.

WELCOME IN THE STATE OF SURVEILLANCE

The data is not only used for business purposes. Since the beginning of the war on terror, many western governments got rid of railings limiting the actions of intelligence agencies and surveillance services. As monitoring of online services become commonplaces, the novelty now rely on using the data for live facial recognition on surveillance video camera streams

The toolbox for crowd and individual control is here. Even if we ignore what the data gathered allow advertisers and governments to do, this simple act of collection is deeply problematic. As the society gain knowledge over this practice, our behavior “normalize”.

The simple awareness of knowing oneself observed will push individuals to modify their behavior in response.

People under scrutiny change their behavior and their choice without even realizing. Because we know we’re watched, we monitor and censor our own behavior. It doesn’t even have to be a conscious process; we’ll simply tend to match the ideals of the watcher — this is called the observer effect.

This phenomenon is present in every academic discipline, sometimes with a different name (Hawthorne Effect).

![]()

This observation was used by the philosopher Jeremy Bentham to envision an institutional building designed for maximum efficiency, the panopticon. Since the watchtower is placed in the center, with prisoners all around, any prisoner can potentially be watched at all times with only one guard. Worse, the prisoners can’t know if they’re being watched or not. He described it himself as “a new mode of obtaining power of mind over mind”.

ADS AFFECT THE VERY CONTENT OF THE MEDIA THAT HOST THEM

Advertisements also affect the media that host them. Some of the effects are quite obvious — such as finding the space for ads (ads break, banner…) but the most damaging effects are also the less prominent ones.

Indeed, because the content is tied to the advertisement, the content creator must follow a “advertiser-friendly” guideline. Media are now competing with one another to host ads, and innovate to attract them: product placement, reality shows… (Publicitarisation — French) Everything is becoming a media (Depublicitarisation). Millions of people are voluntarily following brand accounts on social networks to receive a healthy daily dose of promotion (Hyperpublicitarisation).

In the end, the free supported by ads model is costly. Advertisers are getting close to the media, restricting what can or cannot be said, topics, and schedules. Because of ads, diversity and quality of the media are reduced. But there is more to it. Once ads are running, there is a strong incentive to stay compliant with dominant, advertiser-friendly framework in order to retain and increase revenues.

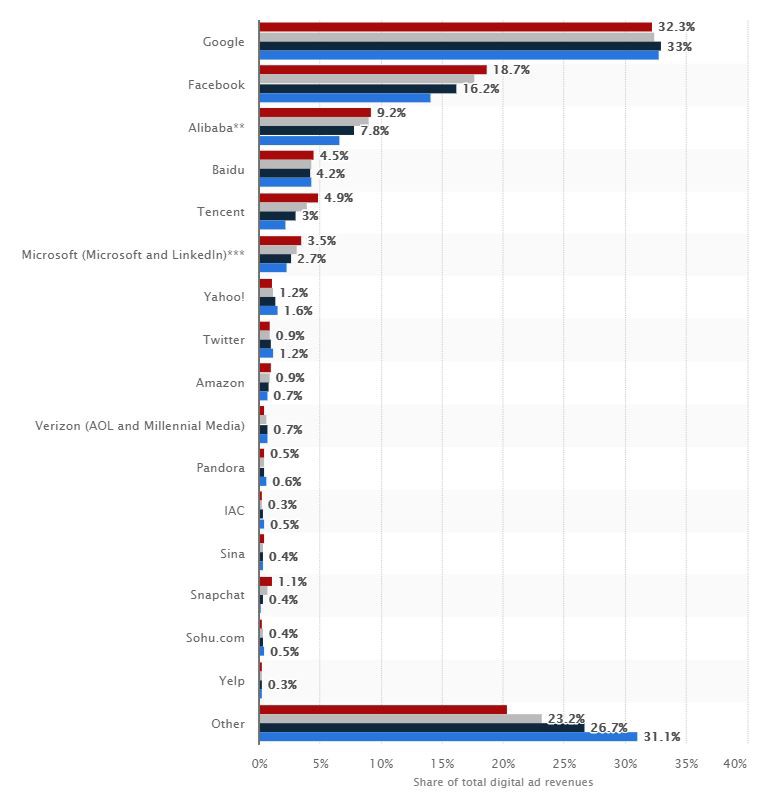

MEANT TO BE BIG

As we have seen already, Facebook’s and others main profit driver is how addicted to their service, to maximize the time spent on it. It can’t be balanced, it’s a design flaw. When Zuckerberg speaks about Facebook’s ideals, and how he wishes to make it more honest and transparent, it’s no more than marketing and PR.On a market where two actors (Facebook and Google) hold more than half of the revenue of the whole industry, what can you do if your ad costs explode? Essentially, you have no alternative.

THE EDGE OF SCALE

I’m not pleading for breaking down Facebook or Google. The result would eventually be the same a few years down the road. Indeed, because of their business model, the GAFA are meant to be giants. Behind the “big data” or whatever name they give to it are basically two things:

- Building a robust system to collect data on consumers, organize it, tag it, and clean it.

- Selling the data after a form a processing (building audience).

Both those activities benefit hugely from scale. For data collection, the bigger you are, the more present you will be which in the end multiply the opportunity to collect new data points. The ideal scenario here would a quasi-monopolistic situation where people can hardly avoid using your service (Hello Zuckie).

When it comes to reselling data, once again size does matter, a lot! Datasets scale twofold, both in terms of quantity and quality. The bigger the dataset, the more people they cover, allowing the data reseller to reach new markets. Simultaneously, each new data point collected on a given individual allows the reseller to charge more, because of the precise targeting and personalization it allows.

Finally, as the dataset covers more and more people, new correlations can be found, which in turn increase the amount of information available in any given person present in the dataset.

What it means, in an economic sense, is that each time Facebook register a new user, it benefits twice from it:

- First, it will increase its total amount of (active) user, which is the base multiplier of FB’s revenues.

- Secondly, because a bigger dataset allows drawing more insightful analysis, FB is able to increase its revenue per user (ARPU) more for each data point it already has on one.

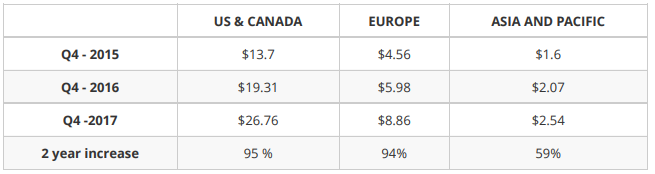

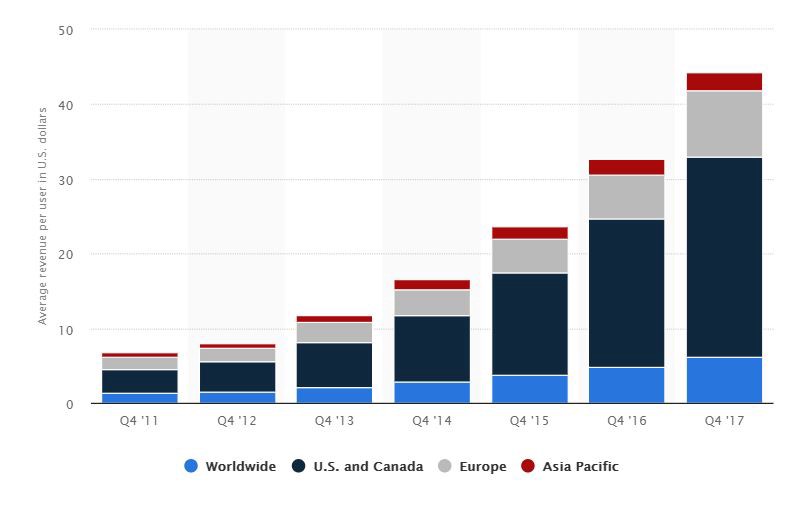

The ARPU (Average Revenue per User) is an interesting metric to look at. It gives you an idea of how much money Facebook is actually able to extract from your data. The ARPU is also strongly correlated on how detailed the database is.

A high ARPU could then indicate that Facebook has a very detailed file. With an ARPU of $26+ for the US and “up to 5,000 data points on 220 million Americans”, it seems to match. Ultimately, the ARPU is an indicator of the extent in which Facebook can be used to influence a population.

If we look at the growth of Facebook’s ARPU, it has been on exponential growth over the last four years. Once again, the real word seems to confirm the observation, as the role played by Facebook keep getting more important with each new ballot.

Facebook’s average revenue per user as of 4th quarter 2017, by region (in U.S. dollars)

Facebook’s average revenue per user as of 4th quarter 2017, by region (in U.S. dollars)

GAFAs are now so big that each of their decisions has huge impacts. Google and Facebook together are the biggest source of traffic for most websites. When Google slashes incoming traffic by 70% to a 20 years old left-leaning website — French, the World Socialist Web Site, it is a political action with real consequences on the political life of the country. GAFAs are now the gatekeepers of the information online and make calls about what we see or not. Because of their size, their decisions have tremendous impacts on society.

Now that we know about Facebook and other online services data collection practices, it’s time call the shots:

Do we keep sacrificing our political power on the altar of convenience, or should we build our own decentralized social network services framework to prevent control and manipulation from hostile parties?

The blockchain opened a range of new options to build decentralized institutions we can trust. Some solutions are already working. We’ll see radical alternatives emerge over the upcoming years, it’s up to us to make the best of it.