Mythology is often used to illustrate DeFi. For example, the Canaanite god Moloch is often mentioned to symbolize coordination issues. Today, I will identify with you a new deity from the DeFi pantheon: Janus.

In this article, we analyze the mechanisms of open governance of DeFi protocols that can lead to the emergence of a new kind of challenge for DeFi, a sworn enemy that I propose to you to embody in the Roman deity Janus.

Much like the two-faced god, a Janus protocol suffers from a deep ambivalence: although it can be an unquestionable success in terms of use, it faces serious antagonisms between its various stakeholders who involve the sustainability of the protocol (users, holders, investors, team and extended community).

To understand the Janus, you have to understand the inherent complexity of DeFi and how it can accommodate consensus on decisions that are deleterious or not optimal. Once the context is set, we can analyze three Janus, each in their own way: MakerDAO, Yearn Finance and Uniswap.

Complexity and governance issues: fertile ground for Janus

The emergence of Janus protocols in the current situation is due to many factors that are difficult to prioritize. I have grouped them into three themes:

Governance and voting mechanisms

The governance of DeFi protocols takes place in an open and transparent way, in several stages.

During discussions on different media such as Discord, the community converges on different ideas that can lead to proposals. Proposals are formalized, usually on governance forums and amended before reaching informal consensus.

Signaling mechanisms (Snapshot) make it possible to identify the most relevant proposals. They are then submitted to the vote of the token holders via the main governance mechanism.

Most governance systems still operate on the logic of 1 token = 1 vote, thus assigning the same weight to all token holders regardless of their attitude towards the project or level of commitment by compared to this one.

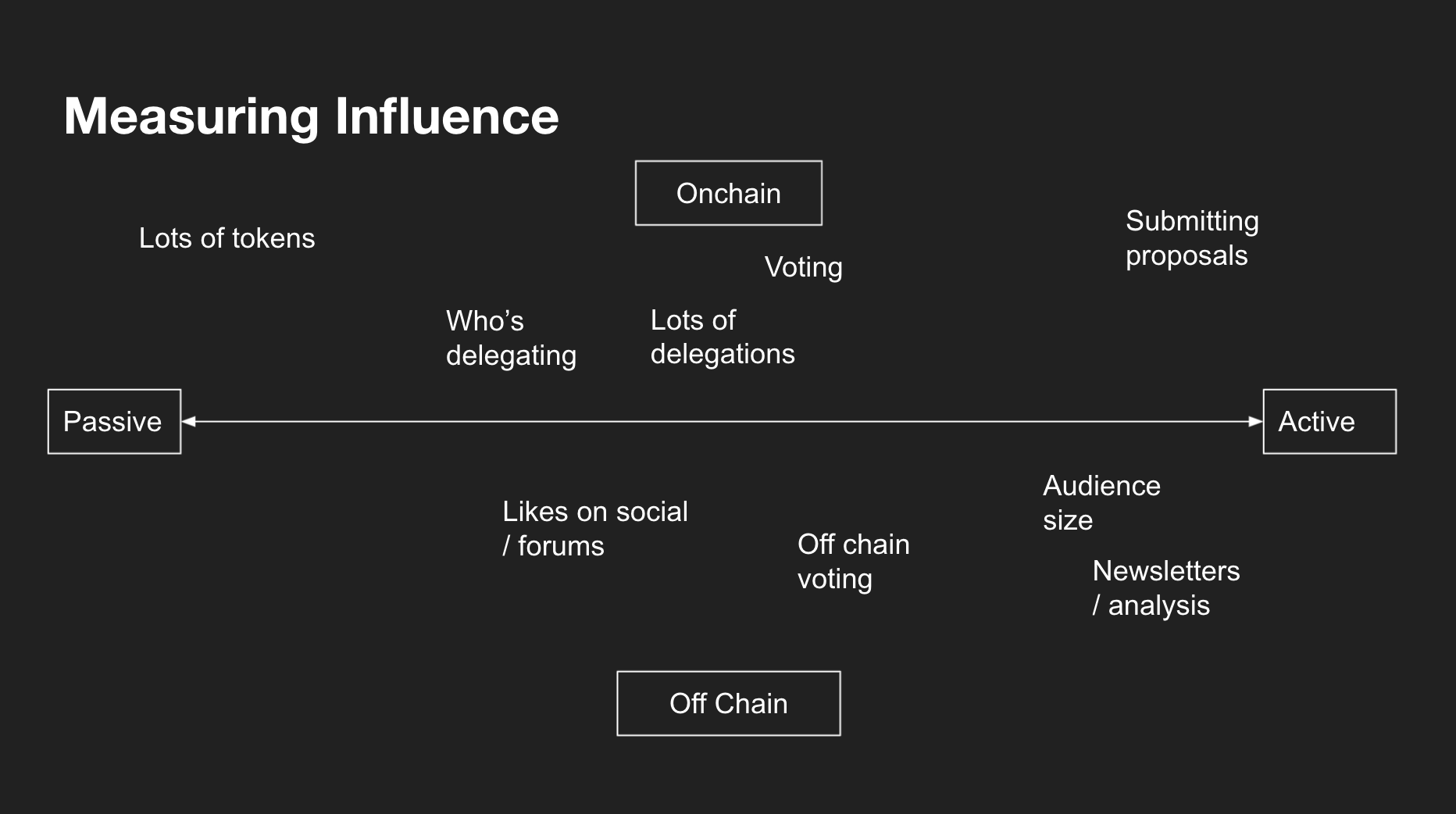

Measure the influence in the governance of DeFi protocols -source

However, some protocols have succeeded in challenging this approach by adding a logic of time commitment: interacting with Curve’s DAO requires engaging its CRVs for a period ranging from 1 to 4 years. A long-term commitment increases the effective voting power obtained (vCRV).

Still, participation is generally low, even when delegation mechanisms are used.

Complexity of decisions

To evaluate governance proposals for a decentralized finance protocol, one must have an understanding of a whole set of basics relating to Ethereum, blockchain and DeFi.

From there, ideally, you need a thorough understanding of the protocol in question, as well as its interactions with other protocols, synergies, etc. We can also now add to this all the additional complexity linked to the multiplication of scalability solutions: sidechains and L2.1

In addition, the formulation of proposals on governance forums is generally quite technical, which makes their understanding difficult and opens the door to manipulation.

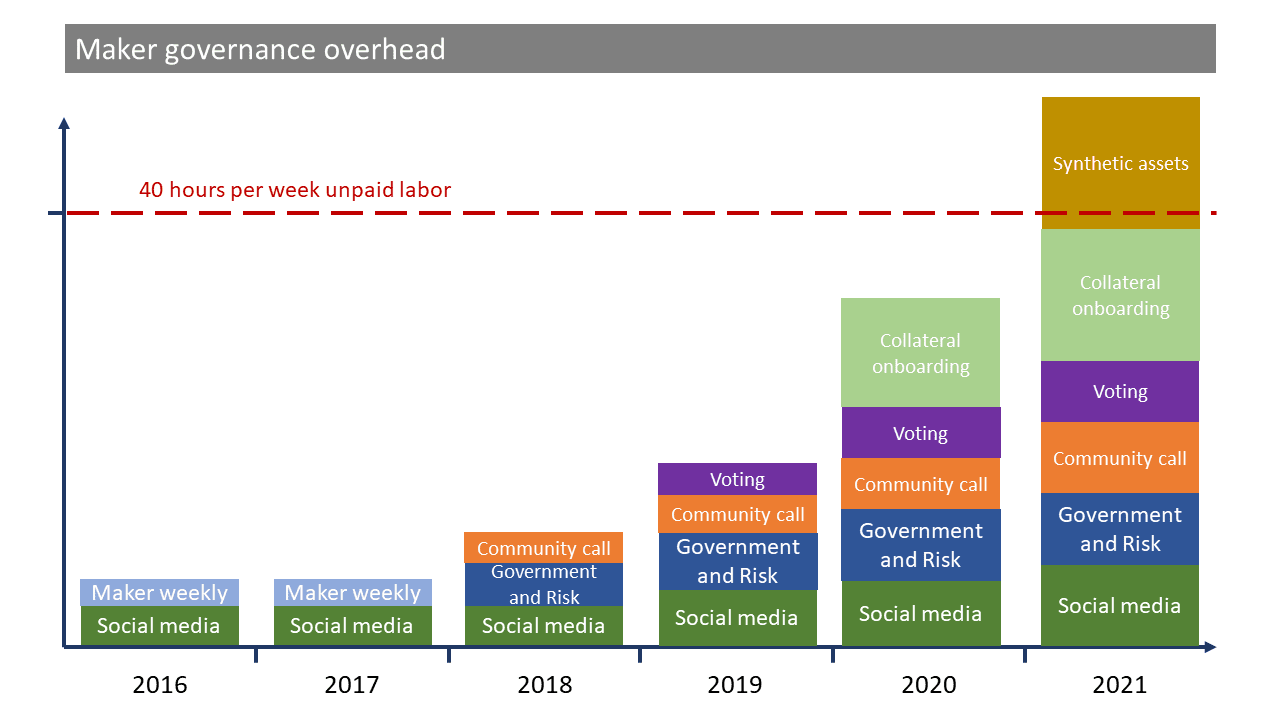

Finally, governance suffers from a real mass effect: as protocols develop, the amount of information to digest to have an informed vote increases accordingly.

A member of the MakerDAO governance forum estimated his weekly monitoring and participation work to be around 40 hours per week, steadily increasing:

Governance supports

Although governance is open and transparent, it still often relies on various proprietary services and therefore administered, most often by the team itself. This causes serious problems.

So governance-related discussions are usually done on Discord and the Governance Forum - both mediums are usually moderated directly by the project team.

Additionally, the team may have control over reporting mechanisms like Snapshot. The accumulation of all these limitations of decentralized governance systems can lead to situations observed recently, where token owners do not vote in their best interests.

This quick tour of the current limits of governance systems was necessary to have the context for what follows. So let’s see the three Janus that I spotted

Uniswap: 1M UNI here, 1M UNI there

Proposal 05 in summary

A rushed vote which resulted in the signing of an almost blank check from 1M UNI for a group of legal directors of large decentralized projects responsible for deploying a DeFI lobbying strategy. Very few transparency mechanisms have been deployed and the influence of the UNI holder community on the funded group is limited.

Proposition 05 Uniswap Gouvernance - DeFi Education Fund

Compression of governance

In the case of Uniswap, it was all there. It all started with a rushed vote as members of the community had many, many questions ignored. The community is concerned about the lack of control over the funds allocated without any conditions. Chris Blec has gathered the main questions and concerns in a letter and managed to get some responses from the team in a Twitter space.

In addition, the organization that will receive the 1M UNI is made up of close members of the Uniswap team and project investors such as a16z are also suspected of having been decisive in the adoption of the decision. The proposal also had direct support from the team.

July 17 edit: quickly after receiving the funds, the multisig sold half of the total balance (500 000 UNI) for USDC, currently sitting idle in the wallet - not even farming!

Finally, the proposal wants to be broader than Uniswap since they are officially mandated to lobby DeFi, but we can ask the question of the vision of DeFi carried by such profiles.

Transparency? Maybe. Control? Hell no !

After the reactions to the first iterations of the proposal, different mechanisms have been added to bring more transparency to the actions of the DeFi Education Fund. The team is also committed to implementing FailSafe as soon as possible. This would allow the DAO (UNI holders) to be able to exercise a veto on the transactions carried out by the multisig.

However at the present time the effective control of the DAO remains limited: the vote has passed and the 1M UNI are now allocated.

This episode corresponds for me to the equivalent of an embezzlement of public funds, except that here the funds come from a DAO. The adventure and its adventures also shed light on the effective power exercised by the various stakeholders in the protocol.

MakerDAO: imbalance of competing interests

The problem with Maker is more general and goes back much further. It is a common problem in DeFi of aligning the divergent interests of different participants. In addition, to respond quickly to the growing demand for DAI, the multiplication of collateral (MCD update) has greatly impacted the trustlessness and effective decentralization of DAI.

Over 60% of DAI collateral is tokens that require some form of trust like USDC, wBTC or TUSD. The problem has been around for a long time and is not going to be resolved, if ever. I have already discussed this problem on this blog, I refer you to this article

Exploring stable assets on Ethereum: approaches & endgame

Abusive user fees

Here, we will rather dig into the problem of excessive fees which illustrates a classic case of rent maximization on customers thought to be captive. 2 DAI being a synthetic stablecoin struck directly by the user, its annual borrowing fees should not exceed 2-3% and this is still costly. Liquity, an alternative to Maker, charges 0.5% annually fees on borrowed LUSD.

Prior to the last update, the main maker ETH vault (ETH-A) was charging 5.5% annual fees. It’s now down to 3.5%, but the fees on the vault closest to Liquity’s borrowing conditions (ETH-B, minimum collateralization = 130% // 110% on Liquity) remains at 9% annually, or 18 times more expensive than its alternative.

Info

Liquity is built with a governance minimization approach, unlike Maker, which may explain part of the huge gap observed between the fees charged by the two platforms.

An annuity for MKR holders?

MakerDAO fees are usually high, even though they’ve been at zero or close for short periods of time to stimulate demand. So why does the DAO Maker systematically vote excessive fees? The answer is as simple as 1 + 1 = 2:

Fees taken from Maker vaults are used to buy MKR tokens in the markets and burn them, making the MKR token rarer.

They are voted by Maker’s DAO, in proportion to the MKR tokens owned.

The very design of the protocol thus encourages MKR owners to vote for extracting the maximum fees tolerated by users, and not a penny less. Indeed, each base point 3 in additional costs translates into more MKR burned and therefore a priori a capital which is appreciated for the owners of the token.

It may sound fabulous in terms of tokenomics because it optimizes for the best possible price on MKR (theoretically), but it is done to the detriment of the users of the service that the platform offers - and therefore goes against the long-term interest- term of the protocol.

You should also keep in mind that unlike most protocols, Maker has never implemented a mechanism to turn its users into holders (liquidity mining). So I hardly see how Maker can be competitive with such a structure.

The ambiguous case of Yearn Finance

Yearn is arguably the simplest and most straightforward example of a Janus. In barely a year, Yearn has become a major DeFi protocol with $ 4B in assets deposited and above all delusional profitability that the team likes to highlight.

However, the story is not so rosy depending on your perspective. We are therefore going to study Yearn’s situation from 3 angles: from a user’s point of view, for another protocol and for the Yearn DAO itself.

Crazy fees for users

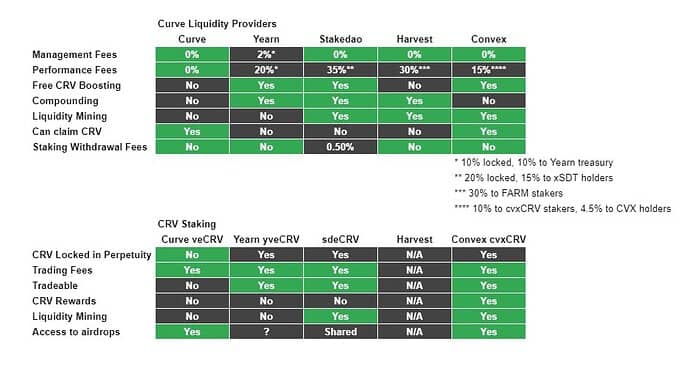

Yearn’s success comes at what cost? Again, essentially users who are literally being robbed by Yearn - fees are among the highest seen for a DeFi asset manager, yet complex:

- Yearn takes 2% annual management fee on the entire deposit.

- Yearn also takes a 20% performance fee: 20% of all farmed assets go into cash. 4

The first charge is the most problematic since it means that Yearn’s excessively greedy charges lead to vaults that… lose money!

Indeed, any vault that does not achieve a minimum of 2% annual return on Yearn ends up in the red once the management fees are taken, without even taking into account the performance fees …

Protocol side: Yearn’s hug of Death

Yearn allows its users to farm different protocols like Curve by automatically managing the composition of their yields.

This is practical for the user, but it also means that ** Yearn systematically sells all the tokens farmed ** by his vaults: we can therefore ask the question of the impact and relevance for the farmed protocol, which is therefore under selling pressure on its native token.

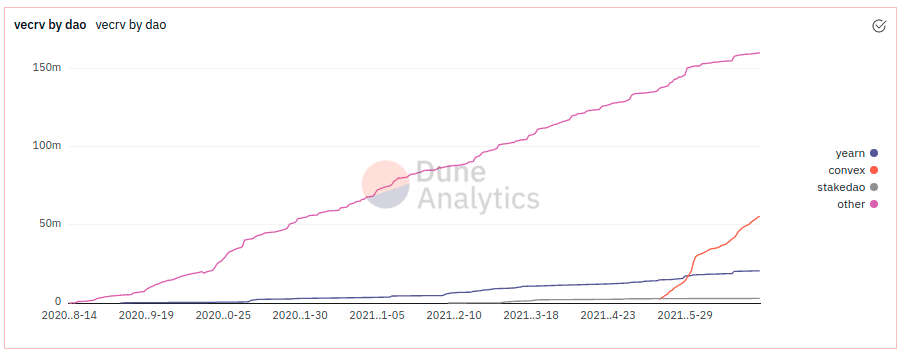

The arrival of Convex has shown that a better structured protocol in terms of tokenomics and specific to Curve can offer a synergistic alternative where the returns are much higher, while avoiding the systematic sale of farmed tokens. I analyze the Convex “flywheel” in this article:🎡 DeFi Flywheel : engineering protocol to protocol synergies through tokens

Thereby, it confronted Yearn with its contradictions and Yearn essentially capitulated by integrating Convex to optimize the performance of its vaults. This now means that Yearn users pay a fee to Convex and help the protocol accumulate more VeCRV and thus widen its gap with Yearn - checkmate for Yearn on Curve.

Overview of the veCRVs owned by the different DAOs - sourceDune Analytics / Banteg

Concerning Yearn DAO

Despite this rather worrying fundamental situation since Yearn now offers essentially non-competitive products (all Curve vaults), Yearn presents itself as one of the undeniable successes of DeFi.

Indeed, the team seems to measure the success of the protocol by the volume of fees collected by it. The indicator is obviously dangerous since with the management fees at 2% per year, any deposit in Yearn systematically pays fees even if little or no profit is made.

Rather than taking the fees charged as an indicator and therefore a measure of success, the protocol could be optimized on the basis of the profits generated for depositors.

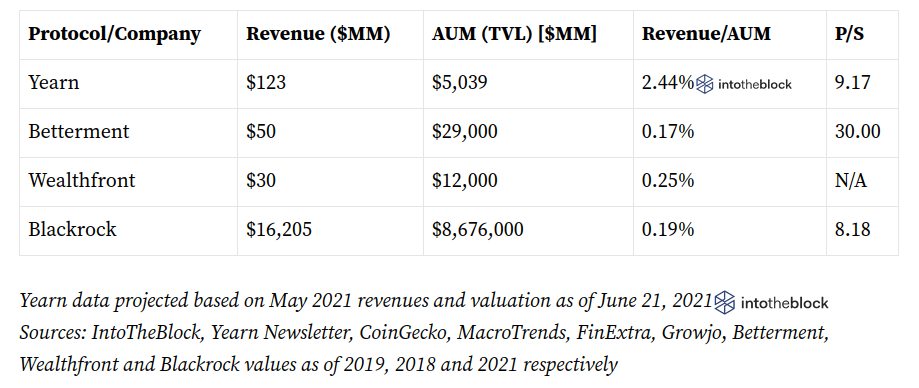

Finally, and even if it is a more subjective topic, the communication around the project is muddled or even almost disturbing at times, for example when Yearn is compared to traditional asset managers like WealthFront or BlackRock - I find that quite unbalanced since Yearn charges similar fees to these structures but operates in a much more dynamic market. In addition, are such companies really relevant models to have in DeFi?

If Yearn compares to asset managers, it may be because the comparison with its DeFi peers is clear:

In addition, where Convex works to allow cvxCRV holders to vote in decisions of the DAO Curve, Yearn is taking control over the voting power associated with CRVs deposited by its users on the yveCRV. The same approach can be observed with the airdrops allocated to VeCRV holders: Yearn grants them to buy CRVs and sponsor their yveCRV vault, while Convex makes them accessible to its depositors.

Are the Janus defensible?

Now that we have set the scene with three Janus, the question of their defendability remains. All three have credible alternatives, often more recent and with more balanced tokenomics. So let’s see how our Janus evolve in relation to these.

In just two months of existence, Convex has already surpassed Yearn in terms of the total value of assets deposited. So far, Yearn’s feedback has failed to turn the tide, and I think only a major overhaul of the model will allow the protocol to remain competitive in the long run.

Nevertheless the machine is launched: Convex already has more than twice as many CRVs as Yearn and accumulates more quickly. And even though Yearn has lots of other protocols, it seems unlikely to me that he will ever be able to compete again on Curve.

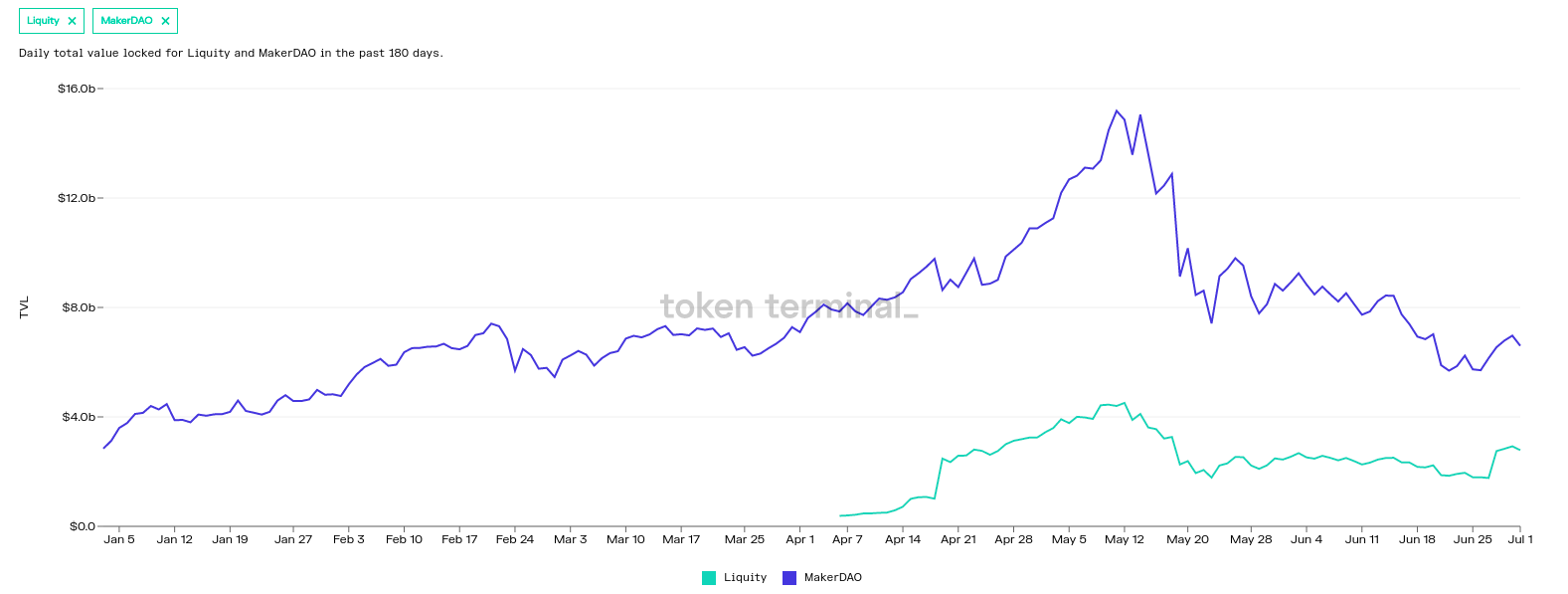

On the Marker side, more and more people are starting to point out the absurdity of the current situation on DAI, and the alternatives are gaining ground. In a few weeks and with only ETH as accepted collateral, Liquity has already attracted the equivalent of more than 40% of the total value deposited in MakerDAO:

On Liquity, borrowing costs are much lower, clearer, and distributed directly to LQTY stakers. The service is thus more open and participatory than MakerDAO while being brutally more efficient. Here again, I think a major overhaul of MakerDAO would be necessary for the protocol to regain its relevance and competitiveness.

Finally, for Uniswap, the competition is even fiercer. The protocol is evolving in the face of mature tokenomics like Curve, which has a protocol revenue sharing mechanism active for almost a year, while nothing is yet offered on UNI.

On all three fronts, I think the situation will force Uniswap, Maker and Yearn to renew themselves. However, with the pace of the industry, the noose is tightening and their more open, efficient and synergistic alternatives are rapidly gaining ground.

As the DAOs of the three protocols fell out of sync with their users, the latter reminded them where their interests lay in the simplest and most effective way we know of: with consistent capital movement. I can’t wait to see what happens next!

🙏 Huge thanks to HHK, Charles, Thomas, Erwan, PhilH & FrenchTony for proofreading the French version of this article and translating it integrally into English.

Take a look for example this pre-proposal taken at random from the MakerDAO governance forum ↩︎

DAI is still seen by many as a decentralized stablecoin that doesn’t require trust, although it no longer does. There are still few stablecoins that rely only on trustless (ETH) and credibly decentralized (or on track) collateral: I know of two - Liquity’s LUSD and Reflexer’s RAI. ↩︎

Financial services fees are often measured in basis point (bps / basis point). A basis point is one hundredth of a percent: 1 bps = 0.01%. ↩︎